|

FREQUENTED and animated mostly by people of our subcontinental diaspora, The Writers Forum is an internet discussion site out of Toronto.

The forum is the brainchild of my friend Munir Saami who over the years has tried to shepherd the written discussions towards literary greens rather than letting them veer into the more belligerent badlands of political brinkmanship or, worse, into the narcissistic pools of personal posturing by self-styled au courant contributors.

A recent flurry of exchanges about the substance and style of postings on the forum got me thinking about the two positions: literary expression and, the more voguish, blog-fest. Some members, basically, accused the moderator of being Nero-ish by insisting on writings with literary merit while, they reminded him — vehemently in some instances — that Swat was burning, citizens were being killed indiscriminately, children kidnapped, foreign cricket teams, hotels and police academies blasted by rocket launchers. You get the idea.

Evidence suggests that, unlike Nero, Saami is neither fond of the fiddle nor did he torch Swat as the famed emperor is rumoured to have done in Rome. If his commentaries are any evidence, like most of us he is rather distraught by the devastating conflagration in our homeland. The Nero reference, in my view, may demonstrate the limitation of arguing by analogy but still carries strong pathos, a powerful emotional force for addressing the increasingly dire exigency that glares at us Pakistanis. So should we all who are affected by the calamitous situation react in frenzied abandon or contemplate and consider in sacred inner spaces, and then express ourselves in language becoming to the gravity of the situation?

I am a sucker for the polemics of the day but in this case I found myself sympathetic to those who thought, no matter how dire the political situation may be, our forum shouldn’t degenerate into the rapidly emerging hyper-animated blogosphere slugfest. The lowest common denominator in any such free-for-all is, invariably, the ad hominem attack which, if nothing else, is a sure recipe for taking one’s eyes off the essential problem.

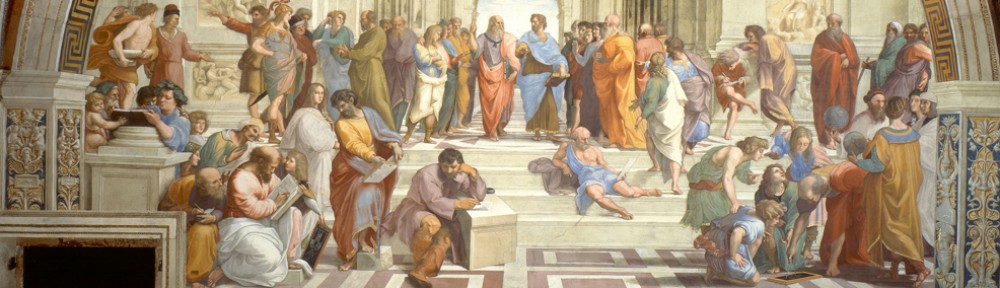

According to Plato, the highest arguments are those that derive their rhet

orical force from genus or definition where the assumption is that certain mutually exclusive classes or essences inhabit the world, classes on which there is consensus, a classification already established and accepted in the mind of the audience. Since The Writers Forum is a literary forum rather than a music or cricket or, yes, political forum, in my view the issue of definition and the forum’s content should be a settled matter. Except that we are still left with the age-old nag about taste and quality in matters literary.

As in most such areas, here too Aristotle provides some guidelines. In Poetics he asserts that literary work should concern itself with form, material, technique and purpose. Surely, all postings on our modest forum cannot live up to these Aristotelian ideals. So, to expand the notion, I thought the contributors might be asked to delve into commentary and informed criticism about the concerns of the day, and literature. Now, literary criticism may be among the most exalted and edifying of human impulses but Matthew Arnold held it to be “a baneful and injurious employment.” I have a suspicion Arnold wanted to add ‘potentially’ in there somewhere but I am not sure.

Since Faiz’s weltanschauung and, more importantly, poetry have been a formative influence of my own stance towards life and literature, I take heart from the fact that literature can subsume politics. Simply put, issues of politics and ideology can be and have been elucidated in literary ways.

For us, the way Faiz utilised the metaphor and diction of Urdu ghazal for such purposes is as piquant an example as can be of this conjecture. Hikmat, Neruda, Darvaish, to name a few, also infused their aesthetic expression with the anguish of their times. As is being done by, I am sure, by men and women who are expressing themselves with tender intelligence, pointed arguments and passionate words in Pushto, Punjabi, Sindhi, Seraiki, Potohari, Balochi, Urdu and a host of other languages spoken amidst the mayhem in our hapless land.

Even though we have seen that political writings can aspire to the condition of literature, they are by definition utilitarian. The use of language in such enterprises is primed to explain, prove, predict and control rather than to express and touch emotions. In political writings, even if language makes appeals to the emotions it does so with the calculated aim of co-opting its readers to its arguments. Literature, however, can address political issues within the ambit of the relevant aesthetic criteria; it does not have to stoop to political writing or media-speak in order to sustain itself or to delight readers.

In our immediate context, I am quite sure people like Intizar, Qasmi, or Faiz — all newspapermen at one time or another, and rather good ones at that — would prefer to be remembered as litterateurs rather than journalists or political writers or even patriots (for by definition, I believe all poets are cosmopolites, their passions and concerns transcend the arbitrary nature of political boundaries). I know my uncle Ali Sardar Jafri, a giant of literary criticism and political commentary and one of the finest literary orators of Urdu, identified himself as a poet; a poet sensitive to the angst of the collective but a poet nevertheless.

The key difference between the plethoric outpourings on the blogosphere and the leisurely pursuit of literature is well demonstrated by Ezra Pound’s pithy comments about literature being news that remains news. Literature, as the cliché goes, has shelf life. Literature’s magic lies in its potential to enlighten and enrapture, to enthral the soul on each immersion. Such magic eludes polemics.

Not too many among us, for example, browse newspapers from the times of the Napoleonic invasion of Russia but some do, still, dedicate their summers to a wholesome immersion in the vivid narrative of War and Peace or the fragrant byways of Remembrance of Things Past. Quratul Ain Haider defined news as that which is hard to sell the next day — it is, she said, hard to dispose of today’s fresh newspapers as raddi (from rud, literally reject) the next day. But Homer sells. So do Tolstoy and Proust. Hafiz of Shiraz and Mirza Nausha of Delhi remain perennial bestsellers.

Immanuel Kant, always a trusted guide in the labyrinths of aesthetics, pointed out that all art aspires to the condition of music. To which let me hazard that all writings, even political writings, aspire to a condition of literature. Some like Faiz’s attain sublimity and become literature.

The writer teaches at Kutztown University in the US and is the author of Honour Killing: Dilemma; Ritual; Understanding.

amirj5@hotmail.com

|