By Muneeza Shamsie

Authors: Dawn , October 01, 2006

(Symposium note: A must read article on a master writer and critic Zulfikar Ghose, with a poem by him on Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan)

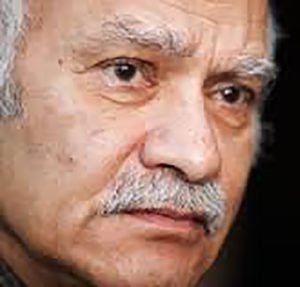

Zulfikar Ghose occupies a unique place in Pakistani letters. He is the only writer of Pakistani origin to have produced such an extensive, varied and accomplished body of English language poetry, fiction and criticism. His one novel about Pakistan The Murder of Aziz Khan had such a powerful impact, that a Pakistani readership of the 1960s still remember him for that one book. In that oppressive era no one dared criticise the state: Ghose’s portrayal of rampant corruption and social injustice touched a deep chord. He described Pakistan’s crude new capitalism of the 1950s and his plot revolved around a poor Punjab farmer systematically destroyed by ruthless industrialists. His was the first cohesive Pakistani English language novel written in modern English and was filled with poetic images about the land and its people, to which he returned with his intricate, eleventh novel, The Triple Mirror of the Self.

“I am very conscious of the art of the novel, he said My literary ancestors go back to Cervantes, Boccacio and The Arabian Nights, and also Joyce, Woolf, Nabokov, Becket. I don’t see any point in writing a novel unless I am worthy of these people. My greatest passion in fiction has been Proust in recent years because of the way he constructs his sentences. I like Conrad because I like his prose. I am not interested in ideas, in the end it is the music of the language that matters.

He is biting in his criticism of current literary hype and the veneration accorded to writers for reasons of geography, political correctness, ethnicity and other non-literary criteria. He believes language and form is paramount and has often said that all he has tried to do is to produce good literature. A contemporary of V.S. Naipaul he is an early example of the diasporic writer who defines himself through the use of language, writing and storytelling. However, people often question his identity: he was born in Sialkot in 1935, grew up in Mumbai, migrated to Britain, lived and taught at the University of Texas at Austin, but writes mostly about South America. Yet he perceives his life as an endless exile from his native land. He writes and speaks with passion about Pakistan and the landscapes of his childhood in Punjab as well as the sense of continuity, history and belonging he experiences when he visits ancient Taxila. He said I would not hazard to guess how or if identity becomes clearer over the years, but it is just a sense of a place to which your soul belongs.

A soft spoken, informal man with a quiet sense of humour, accompanied often by a twinkle in his eye, Zulfikar Ghose was in Pakistan recently, after 16 years, to visit his sisters in Lahore. He gave an illuminating literary talk in Karachi and read new poems, including a tribute to Nusrat Fateh Ali. He spoke a little about himself too. He explained that his father, Khwaja Mohammed Ghaus, frequented Europe on business trips once, but Europeans could not pronounce Ghaus so he changed it to Ghose.

At seven, Zulfikar Ghose moved with his family from Sialkot to Bombay, a city he loved as he did the the wonderful, magical Arabian Sea. He joined the Don Bosco School and his school friends included Shashi Kapoor. Partition coincided with Ghoses near-fatal illness but was traumatic personally because he suddenly found himself regarded as an alien Muslim. In 1952, his family migrated to London. Ghose joined a Grammar School in Chelsea, which nurtured his two great passions: poetry and cricket. He had started writing poetry in India at 14 but the accident of going to England at 17 and to a school where the headmaster was a Shakespeare scholar and English teacher shaped his literary sensibilities. He was introduced to the finest classics and also encouraged to read contemporary writers such as T.S. Eliot and Dylan Thomas. This would not have happened in India or Pakistan, Ghose said.

In 1959, he graduated from Keele University, edited an anthology of poetry from British universities and forged a historic friendship with BS Johnson (1933-73). They would critique each others work and talk endlessly about literature. BS Johnson wrote short stories and I didnt, but we felt nothing was happening with the short story in English: it was stagnant and we should revive it! The arrogance of youth! he laughed.

Ghose and Johnson co-authored a story collection A Statement Against Corpses for which Ghose wrote his first fiction. He spoke warmly of Johnson who became famous as an experimental writer, but shockingly commited suicide. Ghose and his wife, the Brazilian artist Helena de la Fontaine came to London for the publication of Johnsons topical biography two years ago. The couple had married in London in 1964 and Ghose first saw Helenas homeland, Brazil in 1966 and it reminded him a great deal of his own. Interestingly, their work has a similar kinship: the images in his novels and in her works of art often overflow into each other through a rather subtle, subconscious process.

In 1961/2 The Observer sent Ghose to Pakistan to cover the MCC tour. He travelled extensively across East and West Pakistan and felt greatly at home, but could not reconcile himself to military rule. The notion of a paradise lost to tyranny, corruption and greed suggested the plot for The Murder of Aziz Khan. Meanwhile he published a first poetry volume and a first novel, as well as a memoir which reflects the themes of alienation, dispossession and quest running through his oeuvre. His poems appeared in Oxford University Press (OUP) pioneering anthologies of Pakistani English poetry and in the 1972 Penguin Modern Poets 25: Gavin Ewart, Zulfikar Ghose, BS. Johnson. The same year, his third poetry volume appeared. His Selected Poems published by OUP consists of poems written between 1959-1989 which reveal the development of Ghoses increasingly sophisticated verse and its link with the landscapes of his fiction.

He is a distinguished writers writer and does not feel any need to have a literary ancestor from his ethnic background. He declared, I am not an anthropologist, but expressed admiration and affection for the Indian novelist, Raja Rao, a colleague at the University of Texas at Austin. Ghose also spoke of his now-famous literary correspondence with the American novelist, Thomas Berger. He introduced Ghose to many significant books; Ghose recommended South American novelists to him. The most important is Machado de Assis who lived in the second half the 19th century, he said. He is Brazilian and as important as Joyce, Kafka and Chekov and yet he is not known as he should be.

The Ghose-Berger letters, spanning 20 years, are now preserved at the university. Bergers picaresque novel Little Big Man (made into a haunting film) suggested the structure for Ghoses historical trilogy, The Incredible Brazilian which developed from images triggered off by an anthropologists account of 18th-century Brazil. The trilogy received great critical acclaim and was translated into 20 languages; it reconstructs Brazils story through the reincarnations of Gregorio, its narrator. The whole does have a clear subcontinental resonance, but Ghose made the explicit connection between South America and South Asia in The Triple Mirror of The Self which welds autobiographical elements with grand, philosophical themes. This clever, surrealist tale of exile and migration across four continents revolves around the narrators quest for his core, his essential self and takes him backwards in time to Mumbai and ultimately the Punjab: the book begins and ends with mirror images of the Andes and the Hindu Kush.

Ghose compares the process of writing to a spiritual quest, culminating in self-revelation. Discussing his 1998 story collection Veronica and the Gongora Passion, he explained that his story A Mediterranean tale about a boy Abdul Bassam Saeed, who was stolen from his parents in a desert, but rose to great militiary heights and fell in love, began with a sentence that came to Ghoses mind: But by now I have seen all illusions. He played around with it, until it became the storys first sentence, but months passed. He read a lot, while listening as usual to Nusrat and the Sabri Brothers and became interested in the idea of Sufism, beauty and God until images appeared, inspired by the books, music and his own Mediterranean experiences. The subject matter resolved itself and he created a story about the illusion of life and spiritual expression. He added, This is how a story emerges. The first draft showed me what my mind was seeking. Then came the rhythm, the imagistic content and the shaping of the language, which had to have imaginative power.

There is some truly fine writing in Veronica. Each story was different. Brazil, Peru, America, Britain, Spain, India, Pakistan Ghose has gathered up all these countries and a myriad of characters and spun them into this one collection, with that precision and control that characterises his work.

you sang, and the chorus, like a crowd incited

by an orator, repeated the line, its united

voice charged with ecstasy. Then, clapping hands

and a quick sharp prelude on the harmonium,

you broke out with Ali, Ali, Ali–O who can

discover the name of the great God who first

does not call out Ali, Ali, Ali! In the concert

hall even the unbelievers clapped in time

with your chorus, driven wild by your voice,

and saw visions reserved for the faithful.

But then the next thing I hear you are dead.

Life spent devoted to praising God in song,

Gods very breath in your voice, audiences

from Tokyo across Europe to New York shivered

when without knowing the words they understood

your Punjabi, My eyes await your arrival,

for not the words but your voice brought intelligence

of God, your voice, Nusrat, made us all lovers

of beauty and truth, two of Gods names, your

voice raised us and you took us, shy as brides, to Him.

But then the next thing I hear you are dead.

God, this invisible hacker who transmits

a seductive programme, gaudies the brains screen

with visions, only to launch a killer virus! Zulfikar Ghose

POETRY: The Loss of India (1964), Jets From Orange (1967), The Violent West (1972), A Memory of Asia (1984), Selected Poems (1991).

MEMOIRS: The Confessions of a Native Alien (1965).

STORY COLLECTIONS: Statement Against Corpses with B.S. Johnson (1964), Veronica and the Gongora Passion (1998).

NOVELS: The Contradictions (1966), The Murder of Aziz Khan (1967), The Incredible Brazilian Trilogy (1972/75/78), Crumps Terms (1975), Hulmes Investigations into the Bogart Script (1981), A New History of Torments (1982), Don Bueno (1984), Figures of Enchantment (1986), The Triple Mirror of Self (1992).

CRITICISM: Hamlet, Prufrock and Language (1978), The Fiction of Reality (1983), Shakespeares Mortal Knowledge (1993).

Thanks to Dawn: Authors; October 1, 2006

https://web.archive.org/web/20080829131324/http://www.dawn.com/weekly/books/archive/061001/books3.htm