Hello friends,

I am so delighted to share Shaheen’s contribution. Please keep sending more, so that it becomes a Blog for all, by all. Cheers.

—————————–

The Silent Companion

Sitting in a comfortable divan chair in my study, reading a passage from Albert Camus’, L’Etranger, in the front cover page, an inscription by a friend reads: “We are never free, yet, always free. You live in each chapter of each book“, abstracted for a moment from the changing lambency outside the window, my eyes penetrate at my palatial book collection neatly pressed on the mahogany book shelf – essays and books by eminent writers across centuries and seas, I recollect my thought to which book was my first serious attempt at the act of reading – Tolstoy – Anna Karenina – turning the first page was the beginning of my perpetual addiction to reading. But, what, is the act we call reading, which, unfurls, progresses and takes root as a reader?

Dating from the fourth millennium BC, two small clay tablets of rectangular shape were unearthed in Tell Brak, Syria, the indentation represents the number ten and two animals, a goat and probably a sheep. Thus, our history begins with these two tablets, archaeologists believe they are amongst the oldest examples of writings we know. A thought, a voice is conjured up, perhaps a message about ten goats spoken by farmers. Early examples of writing and engravings were found in the grassy savannahs of Central Africa, where people first began drawing on stones and rocks to communicate amongst tribes crossing the landscape. The ancient Mayas, for the vast Buddhist cultures have presented a fascinating comprehension of etching on rock. There were Chinese fortune tellers reading ancient marks on the shell of a tortoise; the public reading the dancer’s movement; the artist drawing a figure of the beloved; the weaver reading the intricate design of a carpet in Persia; the mother reading her baby’s face for sign of emotion; the fishermen reading the ocean currents by dipping a hand into the water — none of these activities required words – did reading come before writing? Societies attributed a system to recognize, decipher the social messages and record its passing. It was with the most literate societies – Muslim, Jewish, Christian and Buddhist cultures, that, reading was a prerequisite at the beginning of the social contract, learning how to read was crucial – in reading the words of God – the worship of the holy book by scroll or paper, hence, one of the tenets of a literate society. Towards the end of fourth millennium the urban dwellers from Mesopotamia developed an art that would change the method of communication between human beings: the art of writing.

As a young girl, I chanced upon a copy of Rabindranath Tagore’s, Gitanjali, in a crowded bazaar in Dar es Salaam, a strange sensation had engulfed as I read a passage:

“What emptiness do you gaze upon!

Do you not feel a thrill passing through the air

with notes of the far away song

floating from the other shore”?

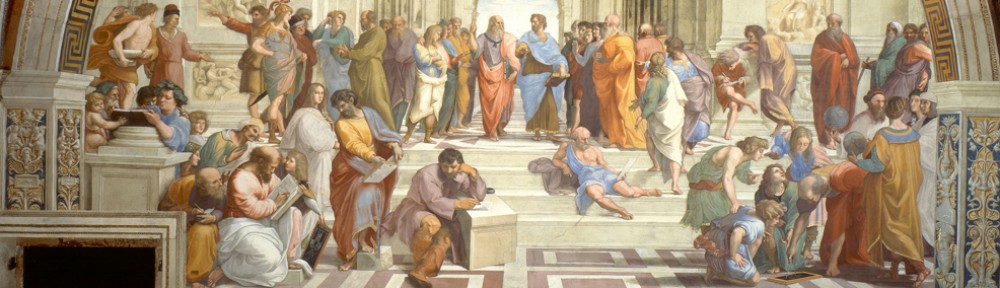

That day I had scribbled a question mark on the tea-stained page — folded and forgotten — only to rediscover it today, twenty two years later: digested, classified, meditated, heartfelt – then I had not fallen in love! Like Plato, I too, acquired knowledge from its subject. In the poignant verses of Mirza Ghalib, Pablo Neruda, Nizar Qabbani, Omar Khayaam, Nasir Qazmi, Dante, Faiza Ahmad Faiz, Mahmud Darwish – there is a an eternal bond with such poets who speak of the crevices in my heart. Reading poetry, political and philosophical essays, literature, metaphysical sciences and history gives me an excuse for privacy — an art of reading at my personal space, where I suspend the external world and engage in the internal landscape – where I could almost hear the silence – it is in my study – most secluded place for reading away from the nebulous arenas that I never feel lonely, the soul finds itself.

Since my family and I lived in various metropolitan cities, there was always a sense of adapting to new milieu; books gave me a permanent home, mercifully, a friendship developed between the chapters of the books I delved in and the comfort of returning again and again to reading. There was no division between the book and I. It was in the words of Karl Marx, Chairman Mao, Bhagat Singh, Patrice Lumumba, Nazim Hikmet, Habib Jalib, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Pablo Neruda, Fidel Castro and Che Guevara that I found a resilient love for both socialism and communism. In Gabriel Garcia Marquez and the greatest of his novels, One Hundred Years of Solitude, there is a instant connection to the characters he prodigiously explores as I have equally relished reading Cervantes, Tolstoy, Gustave Flaubert, Fyoder Dostoevsky, Kafka, and Saadat Manto. Other favorites include, Noam Chomsky, Feryal Ali-Gauhar, Assia Djebar, Yasmina Khadra, Nadine Gordimer are some of the tremendous social-political writers and continue to be the voice of the mute in countries that have suffered war, loss and displacement.

I first kept my books in alphabetical order, by author. This system quickly bored me — how was I to divide between genre? So, I divided by genre: novels, poems, plays. Then as I learnt other languages, I segregated the Spanish and French writers grouping them by language. All the while, there was a euphoria about reading in different language other than English, but, i discovered yet another system by which I categorized as being Communist, censor’s list, police checks in cafes, train stations – the banned authors – Pablo Neruda, Josh Malihabadi, Maxim Gorky, et al. Totalitarian Governments feared reading – in fact, during one of the demonstration organized in Peron’s government in 1950 against the opposing intellectuals, the protest chanted, “Shoes yes, books no.” The artificial dichotomy between society and reading is (still) a continuous problem in many demotic regimes demanding that we forget the harshness of anarchy and do not endorse any opinion on addressing any issues by reading, writing and propagating, therefore these regimes brand and censor books as superfluous luxuries, totalitarian governments impose that we do not think and accept our degradation meekly.

Power exists in the minds of those who are inquisitive and distinguish between the text seen in the mind and the text spoken; by Dante’s power of interpretation; by the Sumerian scribes, imbued the act of reading with political power; by Ray Bradbury in Fahrenheit 451, in which books are carried not on paper but in the mind. And, the Saint Benedict, ordered his monks to hold “if possible” the books they read “in their left hands, wrapped in the sleeves of their tunics, and resting on their knees; their hands shall be uncovered with which to grip and turn the pages.” Once I tried this ritual (without the tunic!), and found knees locked, hence, my idiosyncrasy is revealed by the smoothness of the paper, by its scent, by notes on the sides, a petal of rose used as a bookmark and by certain edition, older the better. Reading and writing have always been my companion – the scent of old books found in second-hand books shops, or, a hand-written letter to a lover, or, composing few lines of poetry on a napkin, or, sitting in a cafe with a Cuban cigar in one hand, reading paperback edition of Rainer Maria Rilke’s – this to me is the art of reading – both re-creates and redefines my world, through the page and far beyond it. I enjoy the sight of my bookshelf – a delight to chance upon in almost forgotten volumes, traces of the reader I once was – scribbles, air plane ticket used as a bookmark, a leaf from a far away summer so long ago, postcard in between pages of a book – those were times when the Internet world was not in sight. Tonight, I pull out one remaining book from that era, a copy of Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde – the words are not to be taken with the lips and the end of the tongue, but, with a throbbing heart – after all, writing depends on the generosity of the reader, the silent companion.